Ellen Forte and M. Christina Schneider

Since 2020 states and educators have begun to ramp up conversations that our current standards and assessment systems divorce our assessment systems from curriculum, instruction, and how students learn. We are possibly seeing a renaissance in the redesign of assessments along with the rejection of some dearly held beliefs about what high quality assessments look like. After we provide a brief history of how we got here, we characterize the problem, and then offer a few ideas about how to fix our foundation to better support students as they climb the stairway to a better tomorrow.

A Brief History of How We Got Here

A seismic shift in U.S. federal education policy beginning in the early 1990s obliged states to (a) build content standards to define the scope of the mathematics, English language arts, and science domains students are expected to learn, (b) establish performance standards to characterize what that learning should look like across a range of sophistication in these domains, and (c) create assessments for each domain that yield scores for use in accountability calculations. In addition to its application to all rather than just some students, this tri-part package was intended to improve achievement through the alignment among the component parts. That is, by setting clear expectations for all students, measuring student performance in relation to those expectations at the end of each year, and holding schools and districts accountable for that performance, we would improve student achievement, particularly among traditionally marginalized groups: English learners and students of color, in poverty, and with disabilities.

The Problem: Embedded Fragmentation

In hindsight, we can see that things have not worked out that way. The experts who build curricula, the experts who provide instruction, and the experts who build tests generally function in silos. They may share common curriculum standards, but not necessarily common understanding and interpretations of them: U.S. Federal Education policy never established a cohesive vision of learning targets beyond the standards themselves. So, the intended alignment of curriculum, instruction, and assessment failed from the outset.

States and assessment developers often share too little common ground about how assessment alignment to standards should be implemented (Forte, 2017). Performance standards as depicted through Range achievement level descriptors (RALDs, Egan et al., 2012) are rarely validated (Schneider et al., 2021) or used to investigate if teachers are providing students rigorous opportunities to learn. Teachers often interpret content standards differently from their intended interpretation and as a result, may measure student learning in the classroom at a lower level of rigor than what states expect (Hall, 2020). They may inconsistently interpret standards with multiple-parts or ignore some parts altogether (Llosa, 2005), and may assign student work (Moss, Brookhart, & Long, 2013) and administer assessments that bear little connection to the rigorous standards-based learning goals that we assume are guiding classroom instruction. Teachers may have some support from the curricula their administrators adopt, but at least one study suggests that some materials teachers use may lead them astray (Polikoff, & Dean, 2019).

What is particularly unhelpful is the commonly held notion that content standards are supposed to function like a checklist to drive curriculum, instruction, and assessment and are entirely separate from performance standards or the integration with other standards. Standards are not of equal weight (Schneider & Johnson, 2019). Because students need to be able to integrate certain concepts and skills to be ready for the next grade, it is important to consider how separate—yet equally important—standards fuse together across the year in one grade and serve as a foundation for the next grade.

Second, validated performance standards (e.g., Reporting RALDs) are central for connecting curriculum, instruction, and assessment. It is not possible to interpret proficiency in the content standards or build tests – either in the classroom or at the large-scale assessment level – that capture the full range of expected student thinking in the content area without some version of them. Performance standards as required under U.S. federal education policy are supposed to define the levels and ranges of sophistication (Schneider & Egan, 2014) and are helpful to teachers when also translated into examples of student work (Hansche, 1998; Schneider and Andrade, 2013). States seldom release examples of student work and the lack of examples of tasks along a learning continuum aligned to RALDs contributes to the lack of alignment between what educators are doing in classrooms and what test developers elicit on tests.

Third, disassociating content standards from performance standards (that is RALDs) contributes to the lack of connection between alignment and standard setting when these aspects of test design should, in fact, be part of the same thing. Alignment is supposed to mean that both instruction and assessment provide sufficient (that is multiple) opportunities for students to demonstrate what they know and can do across the full range of the performance continuum. That is, alignment is intended to help teachers, curriculum developers, and test developers better understand the intent of the standards and how students often develop the skills to get there, emperically. This is the heart of both having an opportunity to learn and an opportunity to show what you know. The alignment evaluation methods we have relied upon for decades have treated individual content standards as discrete elements and ignored the performance standards altogether. How can one say that a test is aligned to the standards without explicitly providing alignment and empirical evidence that the tasks align to the performance standards in truth?

Finally, standard setting is the process for connecting a score scale with the distinctions already inherent to the performance levels as articulated in the RALDs. It is critical to take the time and iteration needed to validate the RALDs so they serve teaching and learning. The field has evolved and is poised to center standard setting as an optimization of alignment of items to RALDs as evidence to denote that score interpretations are true. Standard setting can be contextualized as the empirical validation or disconfirmation of the task-alignment-to-performance standard hypothesis (Lewis & Cook, 2020). With the training of teachers to focus on alignment to RALDs (Schneider & Lewis, 2021) we have additional opportunities to bring coherence and utility of assessment results to teachers and districts by helping them use these same processes to create or evaluate their own district developed assessments and tasks within their curriculums.

Grading student understanding and determining mastery of content with a preponderance of items that align to performance standards at lower levels of proficiency does not help teachers recognize students need more rigorous, complex, and multi-step tasks to grow. Only when we recognize these issues as central to providing each student the opportunity to learn can we take the steps necessary to support assessments as tools to support learning, as we see happening in a handful of pioneer states using embedded, principled design and development approaches (Huff et al., in press).

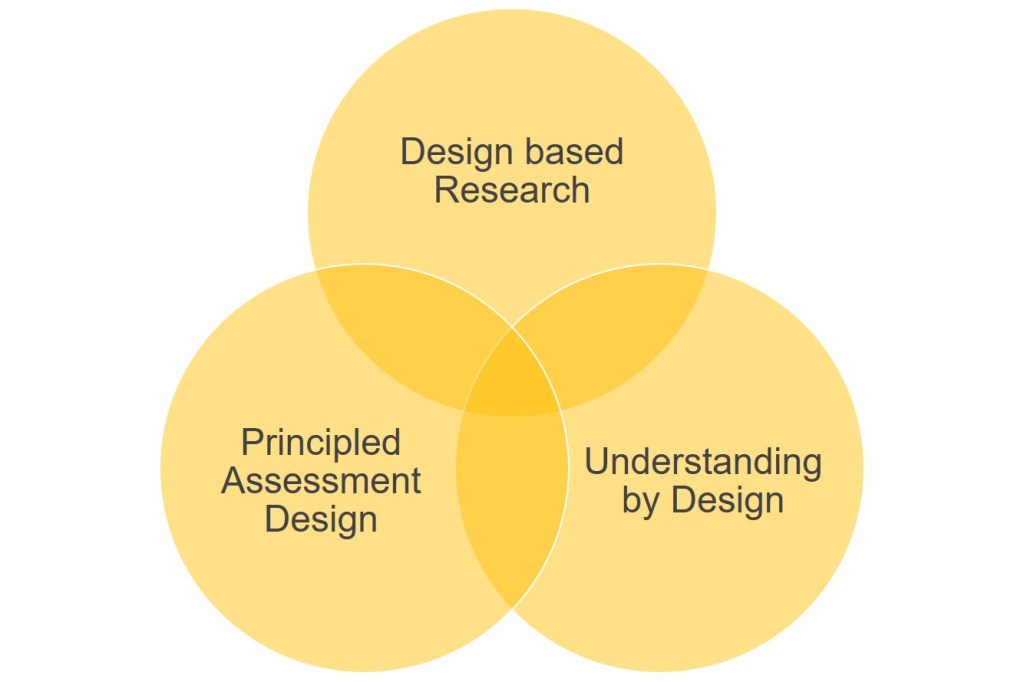

The Solution: Embedded Alignment

Well-implemented principled assessment design (PAD) is centered in a theory of how students acquire knowledge and skills within a course or a school year (Perie & Huff, 2016). Teachers, researchers in the learning sciences, state subject matter experts, and item writers work as equal partners, each group bringing critically important perspectives to the table. These stakeholders collectively unpack the standards and define the contexts, situations, and task features that best foster student learning and allow students to show their thinking as they grow in expertise. This unpacking process moves from standards considered in isolation to progression-based performance standards that integrate the content standards and serve as a firm foundation for building aligned systems of curricula, instruction, and assessment. Field-testing of the tasks that emerge from this process can yield data for alignment checks with the performance standards along with diverse teacher feedback on the utility of the hypothesized progressions for classroom use. This is often possible before the assessment system is used operationally.

It is critical to achieve a common interpretation of growth-to-proficiency across state, district, and classroom assessment systems, centered in an alignment paradigm that allows for resources to be developed that support teachers in internalizing the intended meaning of proficiency. Such resources include open access to task specifications, examples of student work along a continuum of proficiency, and sample classroom performance tasks. These are the kinds of informative resources that support better instruction whether in-person or virtual because they help teachers better understand the state’s definition of proficiency in the standards.

In the federally funded Strengthening Claims-based Interpretations and Uses of Local and Large-scale Science Assessment Scores project (SCILLSS), three states learned first-hand the benefits of embedded alignment and PAD for leveraging change in science instruction and assessment. As a project outcome, publicly available materials were released to support teachers in NGSS-inspired states. Resources from the federally funded Stackable, Instructionally-Embedded Portable Science (SIPS) project show when tasks are aligned to RALDs, standard setting on those embedded tasks using methods that center on alignment to performance standards can provide teachers with three pieces of information to support instructional action:

- “What is the evidence I should look for to better understand where a child is in their sophistication of understanding of the content?”

- “How should I interpret the score on this classroom assessment?” and

- “What evidence should I look for to better understand if a student is growing across time?”

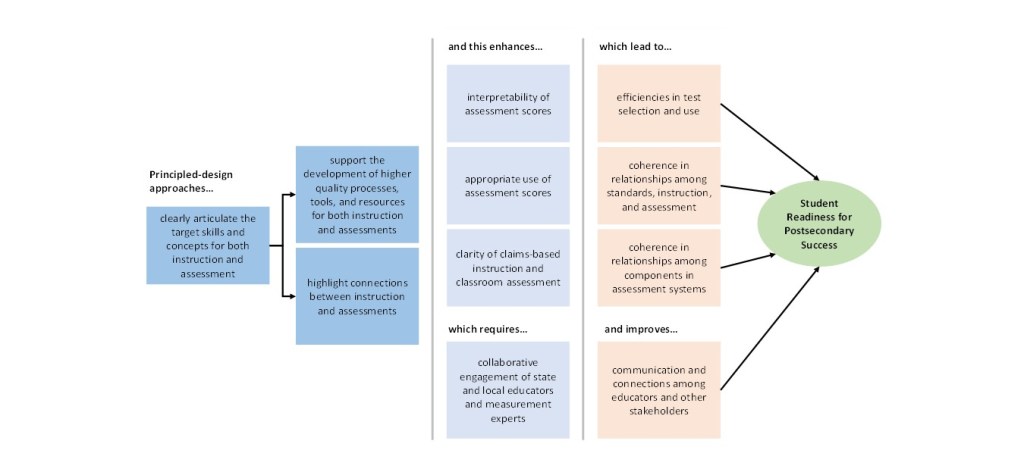

The Theory of Action for SCILLSS, (see Figure 1), articulates the logic for these projects and why embedded alignment is central to supporting a state in creating a context where interpretations of standards are intended to support both classroom and summative assessment. This work continues with the federally funded Coherence and Alignment among Science Curricula, Instruction, and Assessment (CASCIA) project.

Figure 1: Theory of Action for SCILLSS

Conclusion

The purpose of the embedded alignment PAD framework is to cohere interpretations for how students grow in proficiency within and across years; this is a necessary condition if an educational ecosystem is to support achievement for each student and all students whether in classrooms or learning remotely. Partnerships and processes as noted above can change the assessment purpose from the ranking and sorting of students to enhancing instructional practices in real time based on real evidence. Further, engaging educators in every design step brings necessary context to our assessment design and development to ensure all assessments, regardless of use in accountability systems, have a capability of providing formative information.

Ellen Forte, Ph.D., is the CEO & Chief Scientist at edCount, LLC. Dr. Forte’s work focuses on validity evaluation and on policies for how students, including those with disabilities and English learners, engage in instructional and assessment contexts. She particularly specializes in designing, developing, and evaluating assessments for alignment quality. Dr. Forte is the Principal Investigator or Co-Principal Investigator of the federally funded grants described in this blog.

M. Christina Schneider, Ph.D., is Sr. Director of Psychometrics at a major testing company. On the occasional weekend, she enjoys writing her blog Actionable Assessments in the Classroom to provide free support to teachers in identifying evidence of student learning from a progression-based lens. She investigates principled assessment design theory and formative assessment practices in her research, which she and her co-authors have published in a variety of journals and book chapters. Dr. Schneider is a technical advisor for several of the federally funded grants described in this blog.

Leave a comment