Four Key Assessment Use Strategies to Increase Student Achievement

M. Christina Schneider

Moss and Brookhart (2019) in their book, Advancing Formative Assessment in Every Classroom: A Guide for Instructional Leaders, defined formative assessment as a teacher and student collaboration using systematic processes to (a) collect, (b) analyze and (c) take action to improve learning based on diverse types of student learning evidence. In this context formative assessment is defined as using formal and informal evidence to take an action such as changing instruction, providing enrichment, or providing students feedback on actions each student needs to take to own their own learning. Formative assessment is not a type of assessment (or a designation for a classroom assignment) that is weighted less than a summative assessment to produce an overall student grade. Formative assessment is only formative when the student is given the agency to use the information to improve his or her achievement and show and earn credit for their mastery of the learning target. Formative assessment is intended to be an action for improved learning.

Classroom Summative Assessments

Conversely, the purpose of a summative assessment is the evaluation of what a student has learned, and theoretically, it is associated with student and teacher inaction. Historically, summative assessments have been contextualized as assessments for which the purpose is the evaluation and filing of metrics about what a student has learned because both the teacher and the student are expected to move on. The end of semester exam is one such example.

Blurring Definitions

More recently, however, the purposes and uses of formative and summative have begun to blur. Brookhart (2012) discussed commingling assessment purposes in the classroom. For example, a classroom assessment might be administered as an indicator that the student is ready to take a unit or midterm exam, or not. The assessment is not graded; instead, it triggers an action. The student is given feedback; he or she is ready to move forward or should go back and continue to study. Such an approach ensures that students are reviewing for an exam and learning to take the necessary time to study, a needed life-long skill. Conversely, a classroom assessment could be given for a grade as part of a process in which the student has the opportunity to reflect on the work, analyze mistakes, and resubmit for a final summative grade. The assessment is initially graded, but it still triggers an action. This approach is powerful when assignments are real-world, complex, and the standards are high. In these examples, the formative assessment process is a signal regarding where a student’s learning is relative to where the teacher and educational system want the learning to be. The student is given the agency to change his or her achievement prior to the summative evaluation.

The practice test approach I described above is similar to a rigorous university program that posts all course lectures and previous assessments online to assist students in preparing for midterm and final exams. This approach teaches students how to become their own facilitator and evaluator of learning. The second approach is often used when teachers collaborate with students in preparation for external high stakes exams where the quality of passing student work is not a secret and the learning targets are explicitly defined.

External Summative Assessments

Looney (2011) documented many countries have historically provided external summative assessments so that student learning can be triangulated and evaluated uniformly. She noted that it is possible to develop strong external summative assessment systems that can also help shape classroom-based formative assessments and instruction. It is the use of assessment results that drive whether an assessment is formative or summative. And really, should we give any assessment if we cannot use it for formative purposes?

Classroom summative assessments are optimally designed to measure the depth and rigor of the state’s standards at the proficient and the advanced level because this is where the state’s definition of mastery is often centered. You read this correctly. Some standards are not mastered until the student performs at an advanced level, especially if a particular skill is difficult for students. For example, in kindergarten almost every state sets an expectation that students place a period at the end of a sentence by the end of the year. Only the most advanced kindergarten students are typically able to master this skill with consistency and automaticity. States do not always expect mastery of a particular standard to fall in the proficient level in descriptions of performance. If all standards were mastered at a proficient level, how would some students show they are currently advanced when external summative accountability assessments measure students using on-grade content?

State Accountability Assessments

External state accountability assessments are large-scale standardized assessments that provide a snapshot of student performance at a particular point in time. Such assessments undergo rounds of content, bias, and statistical reviews to ensure that test items differentiate among students in different stages of learning. State accountability assessments take their snapshot of student learning at the end of the year when students have had multiple opportunities and time to learn. These assessments are the year-end assessments administered by your state with which most parents are familiar. They use performance levels set by the state’s teachers and policy makers as a central component of reporting.

Performance levels describe different levels of achievement to share how much of the state’s standards a parent or teacher can infer a student has mastered by the end of the year. The performance levels (e.g. basic, proficient, or advanced) are a key feature of describing the degree to which a student has retained what was learned throughout the year. You can find examples of performance levels on any state developed score report.

Increasingly, states ask teacher committees to develop and/or review and refine what are known as Range performance (or achievement) level descriptors. These descriptors define the evidence along the test scale within a standard that teachers and parents should expect to see as students move from more novice levels of understanding to more sophisticated levels of mastery. Second, states ask committees of teachers to provide recommendations of how much content students should know to be considered proficient or advanced using a process called standard setting.

During several standard setting processes, teachers align test items to Range performance level descriptors. Teachers connect descriptions of performance to the test scale in the form of a cut score recommendation. Cut scores demarcate the separation of two different performance levels (e.g., Basic verses Proficient). Cut scores answer the question, “Has the student who achieves at or above this point on the test demonstrated sufficient mastery of the state standards in their grade to be ready and successful in the next grade?” This process allows each student’s test score to be compared to and placed within a performance level that has a policy connotation related to how ready the student is for work at the next grade.

Students who are proficient and advanced are typically considered on track. Students who score in performance levels below proficient likely need additional and more intensive support to help them grow. From my standpoint, if a child does not score in the proficient or advanced range, parents and the educational system might consider using summer break for additional interventions. That is, uniformly as an educational system, we should use these results to take action if needed.

Interim Assessments

Some states desire to take snap shots of student performance during the year to compare the student’s current performance level to the state’s year end performance goals. This is a tool to help teachers and parents monitor progress. States sometimes develop their own interim assessments simultaneously with their accountability assessments to ensure that student learning progress is conceptualized based on the state’s learning framework. Other states prefer to allow districts to determine which interim assessment system they would like to use for snapshots of student achievement. These are state policy decisions. Whereas state-developed interim assessments typically use the same scale as the accountability assessment, district interim assessment providers often statistically link their test results to the state’s test scale based on their customers’ support.

In both contexts, one purpose of interim assessments is to understand if students are likely to be on track academically (i.e., proficient or above) by the end of the year if student learning and instructional pacing remains the same. As a parent or teacher, if you are not comfortable with where the student is likely to be by the end of the year, then you need to change, and likely intensify, aspects of the instructional pacing. Perie, Marion, and Gong (2007) also noted that these assessments can also be used for program evaluation.

As a teacher or parent, the more important questions to ask from interim assessment data follow:

- Is my student still functioning in the same performance level as the last time a snap shot was taken? or

- Has my student progressed in his or her knowledge and skills sufficiently such that the student has likely grown to the next higher performance level?

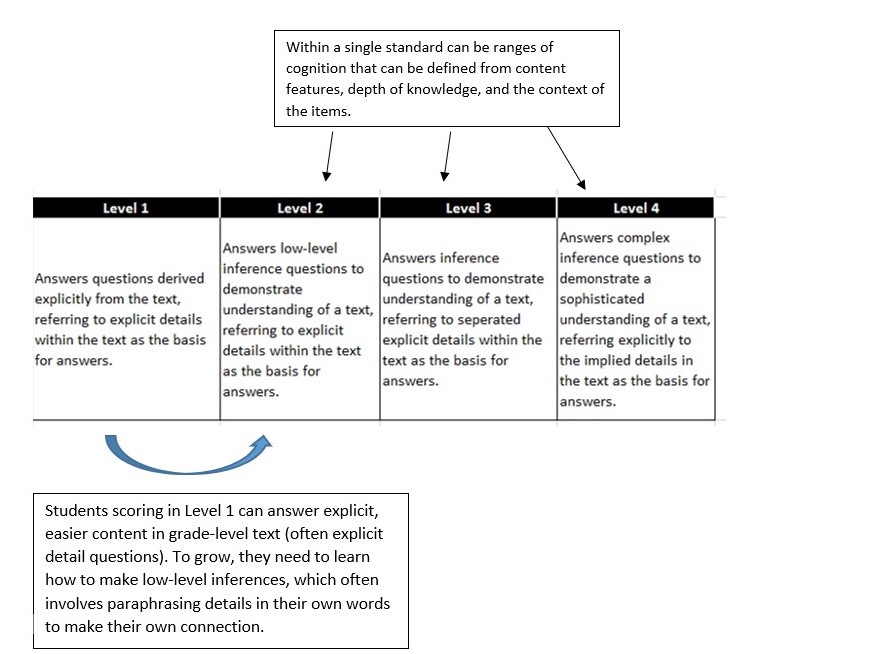

How classroom, interim, and state accountability assessments work as a system should be considered. I find many students begin and end the year in the same performance level. Despite a year of instruction, a significant number of students are essentially stuck in a particular stage of learning. An interim assessment can illuminate that a student is not moving forward when the reporting focus is “where is the student now?” rather than the more typical reporting focus centered on the question, “where will the student likely be by the end of the year?” Understanding in which performance level a student is currently functioning has the potential to help a teacher and parent better target next steps to content or skills that are just above what the student is comfortable in doing as shown in Figure 2. This is because the performance levels are linked to the Range performance level descriptors. Range performance level descriptors provide a pathway regarding the types of tasks students need to master based upon the performance level in which a student is presently performing.

Figure 2: A Range performance level descriptor that shows the evidence a teacher can use to find tasks that scaffold a student to proficiency over time.

Four Steps for Creating Action Plans

We often think students are successfully learning if they answer 80%–100% of the questions they are given correctly. The reality is that scores this high on homework and classwork mean the content is too easy. Essentially this is an indicator we have provided students with content they have already mastered. For a summative assessment, this is certainly a desirable index. However, if we want to grow student achievement, students need content they can answer correctly at the start of instruction between 40%–60% of the time. This is the content the students are in the active process of learning but have not yet mastered. Students need multiple and sustained opportunities to move to mastery. When we consider that classroom, interim, and accountability assessments should work as a system, we need to attend to what desirable indexes of success are that should drive formative actions based on each assessment type and reporting metric.

- State accountability assessments can be used by districts and parents to determine if additional instructional support for a student is needed. For students who are not yet proficient, summer is a great opportunity to engage in additional learning with your student. There are several websites that offer free instructional resources with videos across grades and content areas you can investigate. Some of these resources pre-test students to help identify where students should begin summer work. Districts might engage in research studies to determine which students might benefit from instructional resource subscriptions over the summer and which students are better served by contact hours through summer school programs with teachers. Metrics based on moving students at least one performance level are likely helpful to parents and teachers so they can determine the intensity (i.e., the suggested number of hours per week or suggested number of learning modules) of intervention needed.

- Interim assessments can identify a student’s current stage of performance and help parents and teachers recognize if students are stuck in the same stage of learning across time so that interventions can start earlier in the year. If the student is in essentially the same place in the fall and winter, it is time to provide the student with additional support, perhaps adding on after school programs that offer homework support in particular content areas. If you are a parent, ask your child’s teacher for his or her interim assessment score reports so you are aware of how your child is doing across time. Students will score in lower performance levels early in the year. Don’t be alarmed. It is when students are not moving forward after the second administration you want to encourage action.

- Accountability assessments often provide Range performance level descriptors that can be used by teachers as an informative tool to identify if they are providing students with tasks that align to proficient and advanced levels within standards during instruction, homework, and assessment occasions. They connect what is done in the classroom to the state’s learning framework. Range performance level descriptors can help teachers identify in the classroom where a student is likely functioning along the proficiency continuum. Range performance level descriptors, when used correctly, can provide teachers examples of how to scaffold tasks for the same standard from easy to more difficult. My next blog will outline more information about this.

- Classroom assessments can be set up as formative indicators to help students evaluate if they need to engage in additional work prior to a summative assessment. Classroom assessments are often set at the pace of the teacher by necessity. The reality is that students do not learn at the same rate. Students need tools to help them self-assess if they are ready to move on to proficient and advanced tasks at least a week in advance of a unit test. Adding instructional videos help students who do not remember, even with notes, all the steps for more complex tasks. The teacher can set up practice assessment benchmarks that align to feedback such as the following:

- A score of 0-18 means you need additional study and practice prior to the unit assessment.

- A score of 19-25 means you are likely ready to proceed to the unit test.

- Use the video resources to reinforce what we learned in class.

State accountability assessments have the primary purpose of being a measure of what a student has learned; however, it is feasible and desirable for a well-balanced system of assessments to have defined formative actions when students are not growing over time in their learning. What interventions look like can be tiered as student evidence of learning is collected, analyzed, and research is conducted to optimally provide the right level of support at the right time to increase student mastery.

Leave a comment