There is growing consensus that a single end-of-year assessment provides student learning information too late to be instructionally supportive. For this reason, roughly 25% of states are moving to or piloting some type of progress monitoring assessment system to help determine if students are growing during the year. One of the reasons I advocate for and love supporting states constructing their own progress monitoring systems is that such an approach has the potential to provide teachers information regarding where students are now compared to year-end standards using a common framework for interpreting student thinking across assessments, curriculum, and instruction. I wrote about how to conceptually do this in 2021 in three blogs:

- Synergizing Assessment with Learning Science to Support Accelerated Learning Recovery: Preamble

- Synergizing Assessment with Learning Science to Support Accelerated Learning Recovery: Principled Assessment Design

- Synergizing Assessment with Learning Science to Support Accelerated Learning Recovery: Understanding by Design.

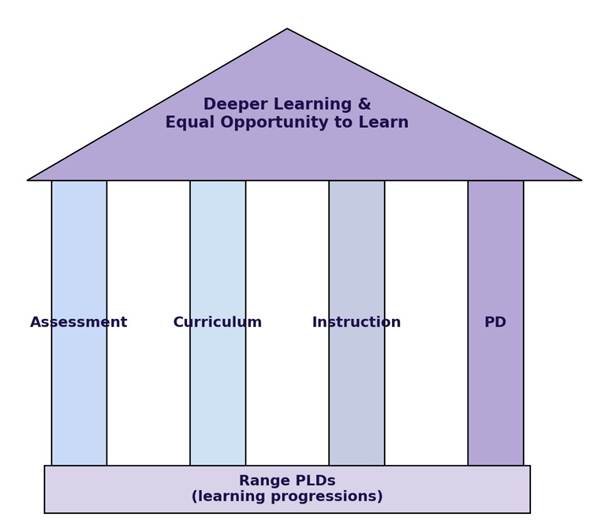

Accelerating student learning at the system level takes time. And I neglected to think through the systemic professional development supports that also need to be created to support ensuring teachers are confident in knowing how to take action. The reality is that creating a comprehensive, coherent, and instructionally useful assessment system requires a multi-year, multi-pronged approach that actively involves stakeholders across all levels of the educational ecosystem and includes classroom instructional and assessment tasks as well.

Figure 1. An integrated, balanced assessment system based in validated Range PLDs CC by 4.0

What Can We Learn from a Through Year Assessment?

Long ago, a wonderful first grade teacher spent a week at the beginning of the year giving a student every end-of-unit assessment in first grade mathematics. Her conclusion was the student needed touch-up instruction in two areas of the curriculum and then the student could be moved forward to the second grade curriculum. The only acceleration option was to place the student in an online, self-paced curriculum, but the teacher rightly noted the need of social interaction in the learning environment. She worked to balance the two. After seeing the intensity, time, and logistical feasibility of deeply investigating what a student can do in real life, I know it is not feasible for every teacher to do this with every student. But this student is not alone.

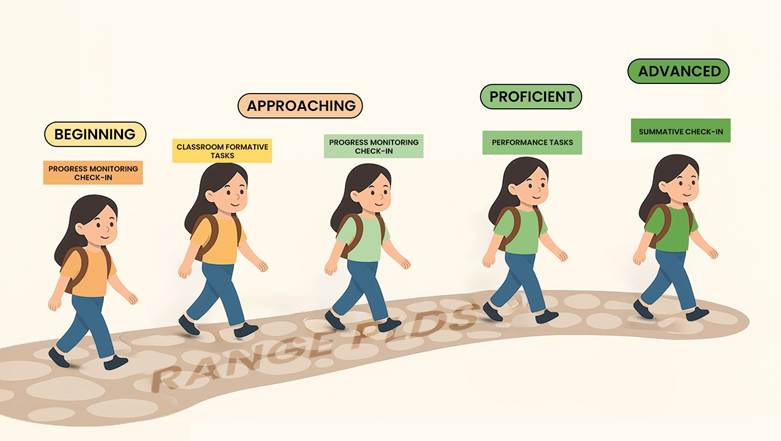

Based on state through year technical reports, between 2% to 20% of students in particular grades and content areas may already be proficient or above in the standards at the beginning of the year. In English language arts, for example, between 2%–7% of students are predicted to be in the Advanced level. Advanced students, who have already mastered the state standards for the year on the first assessment, need the opportunity to grow in the adjacent above-grade standards. Proficient students need to remain in the grade-level curriculum and grow to the Advanced level to support rich college and career readiness, with teachers providing instructional tasks at the advanced level. This is the beauty of a through year assessment system that bridges the purposes of interim and summative assessments. It provides a state developed progress monitoring system in which the interpretation of mastery is held stable across the interim and summative assessments.

Planning future instruction is one of the three types of possible instructional actions teachers can make based on assessment information (Evans & Marion, 2024). Obtaining the likely achievement level of students now based on interpretations of where the student is compared to year end standards in a day, at the beginning of the year, helps teachers (a) determine locations in the curriculum that students may need to begin instruction, (b) determine which students need what types of tasks by difficulty or (c) determine the level of scaffolding students may need to support them accessing advanced tasks. These actions can be three different ways to differentiate for students, though there are others. Through year assessment information is instructionally useful and formative if teachers use the information to take an action that is different than the action they would have taken without it (Black and Wiliam, 2009).

Large-grain-size assessment information with proficiency level determinations of Proficient or Advanced in Grade 3 English Language Arts can be coupled with validated, qualitative descriptions regarding what test scores mean in terms of thinking skills and content skills in different regions of the scale (i.e., Range performance level descriptors or Range PLDs). Together these pieces of information provide support to teachers and students by depicting what Kristen Huff recently described as, “chunkier versions of learning progressions… they clearly articulate major developmental shifts and milestones in learning.” Through year assessments have the potential to serve as pre-assessment information. Although Moon, Brighton, and Tomlinson (2020) contextualized pre-assessment in the context of classroom assessment (before a unit is administered), through year assessments with validated Range PLDs can identify what students likely know so that more nuanced “where do we begin” investigations can efficiently occur for students at each end of the performance continuum. This approach can be important for states with district-level stakeholders who want to retain control on which standards to teach when.

What Can We Learn from a Through Course Assessment?

A few states have done something unthinkable 10 years ago. They have gained consensus across district stakeholders on a common framework regarding what standards should be taught in particular parts of the year. They have, in essence, sequenced their standards into a within-year macro progression. The through course assessments measure how much students have learned of a subset of specific standards that should have been taught prior to the testing window. These are assessments that are intended to be closely aligned to the enacted curriculum, return test results quickly, and possibly provide information on which standards students need additional time and opportunities to learn. This approach to an assessment, while not measuring growth along a test scale, can provide more robust information about where students are functioning in relation to specific standards that were more recently taught. Teachers can triangulate this information with their classroom instruction. Teachers like this approach, especially when states provide replacement units centered in aligning scaffolding and tasks to validated Range PLDs.

The Importance of Understanding Your State’s Task-to-Standard Alignment Model: A State’s Alignment Framework

Different pictures of student proficiency can emerge across assessment sources and curriculum materials due to the complexity of what it means for tasks (assessment and instructional) to be aligned to state standards. My colleagues, Karla Egan, Marc Julian, and I wrote the way items are aligned to assessments is central to test score interpretations gleaned from any assessment. The item alignment policy model a state uses in its state assessment program (i.e., how tasks that are developed to match standards) is central to how a state desires teachers to interpret and measure standards in the classroom. This is often a missing communication element when standards are released; however, there are some states that provide exemplary support in this area.

States use different item alignment policy models. Historically Webb’s (2005) depth of knowledge (DOK) model has been the most commonly used item-to-standard alignment framework on state assessments. (I personally like to use Hess’s Cognitive Rigor Matrix when working with teachers on projects.) In the most common policy model, 50% of a test’s items have to be aligned at or above the cognitive level of the state standard (Webb, Herman, and Webb, 2007) to achieve depth of knowledge consistency. Under this model, the state standards represent the minimum a student should know and be able to do at the end of the year. That is, a student is expected to grow to and beyond what is specified in the standards during the year. This alignment model can be helpful for thinking about how students grow, and we have found DOK is a predictor of task difficulty through research.

Some states use a policy model requiring that items on the assessment match the implicit DOK level specified in each state standard. Under this model, the state standards represent the maximum regarding what a student should know and be able to do by the end of the year. This alignment model is centered in an end-of-year mastery paradigm. It is less useful for instructional differentiation in a through year system because it does not encourage the development of items to identify where students are in their journey of thinking in relation to the standard. Rather, the goal is to identify an end state for a particular grade.

Performance level descriptors (PLDs) are the statements that represent score meaning. Although standards-based achievement tests yield many types of scores (e.g., total test scale scores)… the performance level is at the heart of all interpretations and uses in the standards-based context.

This statement has evolved to a new item alignment policy model in which some states create and match their items to the Range PLDs. This approach allows states to depict standards-based learning progressions as an interaction of cognition changes, content difficulty, and contextual features which provide content scaffolding up to support student growth to advanced tasks.

Applying a State’s Alignment Framework in the Classroom

Using the Range PLD-to-task (item) alignment model in the classroom can help teachers

1. think about how students grow across time so they can coach and facilitate learning from a student’s current stage of thinking to the proficient stage and beyond

2. represent where end-of year mastery expectations are placed, and

3. predict which performance level the task they provide in the classroom would be aligned to on the proficiency continuum which is a social moderation approach of linking classroom assessments to progress monitoring measures.

Validated learning progressions also help teachers recognize what advanced student learning looks like. In their book on using differentiated classroom assessment, Moon, Brighton, and Tomlinson (2020) advocated that instructional planning and tasks should target the advanced level with appropriate scaffolding in place to support all students in accessing them. Hess (2023) encouraged strategic scaffolding to support students when providing them rigorous performance tasks. She noted rather than a one size fits all scaffolding approach, a teacher should choose the right type of scaffolding for the student’s needs to reach the deepest level of rigor – or the ceiling of the standard. In these scenarios, the ceiling is represented as the advanced level of the Range PLDs.

If there is not a transparent item alignment process that is shared with teachers, it is not unexpected that what is taught and measured in the classroom may differ than what is measured on interim assessments and summative assessments. Validated Range PLDs can be the foundation across a system that brings coherence to a balanced assessment system: they are the “glue” that makes things understandable or cohesive, whether the assessment is a performance task in a classroom or on a state assessment. Alignment of assessment tasks to Range PLDs is critical for teachers to understand if a state is going to create a comprehensive, coherent, and instructionally useful assessment system. They allow districts to conduct alignment studies on tasks within their curriculum. This helps districts consider the question, “are all students being provided the opportunity to reach proficient and beyond?”

Analyzing Opportunity to Learn

Once a foundation regarding how students are likely to grow is established, district and school leaders have the opportunity to examine their curriculum for rigor by matching the tasks students are provided to the Range PLDs. Teacher committees can be convened. In a random sample of units, committees can identify what each task measures and write a description. They can then match the task to the cell in the Range PLDs to determine which level of the Range PLDs the task aligns to. The alignment to the Range PLD cell also provides the alignment to the standard.

A curriculum should have tasks that span the range of the PLDs within a standard if it is measuring the full depth of the standards. It also needs to provide consideration regarding what precursor skills students need. When the majority of tasks align to the lower levels of the Range PLDs, a district may wish to consider if replacement units or replacement tasks are needed as a supplement. All students should have the opportunity to show what they know. All students should have an opportunity to grow. This means thinking about where instructional tasks and classroom assessment tasks are targeted and how they foster opportunities for demonstrating proficient and advanced thinking. It is also important to investigate the percentage of tasks that are authentic constructed response item types versus multiple choice. Formative assessment processes, where student work can be analyzed, take more time but have a higher value for classroom learning processes.

Sustained, Paid Professional Development for Teachers

Meutstege et al., (2023) investigated how expert teachers work to differentiate instruction. Teachers indicated it is important to think about how to attend both to the students in novice stages and advanced stages when creating lessons. Meutstege et al. found that the expert teachers in their study chose assignments they perceived as varying in complexity to adapt to the differing learning levels of students within learning goals. This approach aligns to instructional differentiation frameworks from Moon et al. (2020) who argued that both assessments and lessons should be slightly more difficult than what a student can currently do. That is, curriculum, instruction, and assessments that are too difficult or too easy are equally inappropriate for helping students grow. Students need tasks that are at the right level of difficulty above their current ability. Thus, teachers need states to provide training on matching, developing, or adapting tasks to different levels of rigor within the standards and also on how the state interprets its standards. Authentic classroom examples and replacement units that are available for teachers to see, coupled with the predicted task difficulty, can help teachers see that a task can be fully aligned to a standard, but not at the state’s intended level of rigor for it to be considered proficient or advanced.

Aligning Assessment, Curriculum, Instruction, and Professional Development to Support a Common Lens of Interpreting Student Work

State leaders, working to understand the needs of district leaders and teachers, with a through year or through course system, understand that to improve student learning, a multipronged, multi-year approach is critical. First, as assessments are being developed to intended score interpretations, the accuracy of those interpretations needs to be monitored. When the success criteria are not met, this means the stages of student learning are not yet sufficiently understood to be useful for guiding item alignment, curriculum goals, and classroom instructional tasks, so iteration and rework need to occur. Once success criteria are met, states can support district leaders and teachers in understanding what alignment frameworks are and how they work through professional development. Ensuring curriculum and classroom instructional tasks allow students to show what they know and stretch their thinking is a critical component of improving student achievement. In order to allow districts to engage in audits of their instructional materials, they need a framework that aligns to a state’s construct. They need professional development. Once audits are complete and gaps in students’ opportunities to learn at proficient and advanced levels are located, the deep work of replacement units and sustained professional development can occur through the development of performance tasks, formative assessment professional development and strategies, and more targeted, differentiated student opportunities to learn can begin. The work described above is not fast. It involves sustained focus, patience, and perseverance. It involves paying teachers for their professional development time and follow-ups. It also means trusting that once teachers understand how this process works, they will engage in assignments that require deeper learning from students at higher levels of complexity. This process is distilled in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: From Balanced Assessment to Integrated Learning, figure created using ChatGPT

From my large scale multi-year evaluation of a professional development program for teachers with co-author Patrick Meyer, I learned that teachers need additional support on who needs additional opportunities to learn and what those opportunities look like, especially for students in schools of high poverty. During this and subsequent work, I learned how much time and how difficult it is to develop a common vision regarding what a proficient task looks like and what alignment to standards means at scale. In creating a through year (or through course) assessment system, a state can establish what proficient and advanced student thinking looks like (a theory of learning), and it can provide information on what evidence teachers and district leaders should see in tasks in high quality curriculums and instructional materials. It can provide training and support on alignment processes districts can use to uncover potential gaps in providing students with sufficient opportunities to learn. District leaders then have to engage in audits of their curriculums and provide teachers the sustained professional development time to develop richer instructional and assessment tasks to better guide and progress monitor student learning. When such an approach is used, we will no longer need to discuss balanced assessment systems. We will have transitioned from siloed assessments to integrated learning systems.

Interested in Resources to Help you in the Classroom?

If you want to learn how to create tasks that are designed to provide scaffolding and supports to tackle performance tasks consistently at higher levels of complexity read Rigor by Design, Not Chance: Deeper Thinking Through Actionable Instruction and Assessment by Hess

If you want to learn how to create linked assessment tasks to a progression of learning and how to use that information to place students in tasks just right for them, read Schneider & Johnson’s Using Formative Assessment to Support Student Learning Objectives.

If you want to learn about frameworks that support differentiated instruction with the intent of growing all students read Moon, Brighton, and Tomlinson’s book, Using Differentiated Classroom Assessment to Enhance Student Learning

If you want to learn about embedding assessment tasks into a curriculum, read Understanding by Design, by Wiggins & McTighe

Leave a comment